|

|

|

|

|

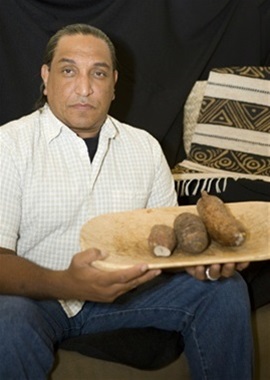

By Jorge Baracutei Estevez

Cacike Jorge Baracutei Estevez Concatecuax

Cacike Jorge Baracutei Estevez Concatecuax

Photos by: Jorge Baracutei Estevez & F. A. Mota May 22-May 3, 2013 MISSION PURPOSE: The purpose of this trip was to explore and

investigate the Indigeneity of the Dominican Republic. Visiting remote mountain towns and villages, we hope to record, photograph and document Indigenous communities and individuals on the island. Further our hope to bring awareness of the NMAI and SLC’s

Caribbean Indigenous Legacies Project to the people of the Dominican Republic. Report: This trip was insightful and informative on many levels and it is my wish to be able to convey all that I learned and witnessed.

My main purpose was to explore the sense of suppressed Indigeneity of the Dominican Republic . One general thesis for the general research effort is that there is consciousness and continuity of an indigenous identity and ways of being, even as people often

don’t reference this directly. We explore this as part of a shame-fear complex. A second purpose was to gather a brief survey of Taino nomenclature and other associated ‘monte’ behavior that corresponds with early Taino culture as reported

in the chronicles of contact period. The Dominican Republic was the first island settled by the Spanish under Christopher Columbus. It was the first to have prolonged contact between the Native Taino Indians

and the Europeans. It was on this island that the myth of Taino extinction began. Given the plethora of historical literature claiming the total annihilation of the Indigenous people of the island, it comes as quite surprising to many people that there is

indeed a substantial native presence on the island. As a descendant of indigenous families from the island, and identified as Taino, I have had to live a lifetime with historical inaccuracies and contradictions about

my people. I am glad for the opportunity to join in the explorations into the questions of this project.In particular, I pick up on a range of personal knowledge of places and families where the “indio” identity sustains. This trip provides

some leads and preliminary evidence. Of course, a longer sustained research project is necessary to fully elaborate on the complexities and extent of Indigenous cultural, linguistic and biological survival. May 22, Day 1- Santiago-Tubagua

I left New York City at 7:30 a.m. and landed at Santiago Airport at 11:00 a.m. where I was met by old friends and my camera/guide crew which consisted of Boynayel Mota (Afro-Taino) and Carolina Cofre (Mapuche). We began

working immediately. We first drove to the home of Mercedes Villejos who graciously loaned me her vehicle for 13 days. INVITATION FOR FUTURE: Her only wish was that I would visit her community of Janico, where she claimed

many Indian customs could be found. Sadly, this was not on my itinerary and I was unable to oblige. In the late afternoon, we headed to the mountain towns of Yasica, Cumbre, Quemado, and Tubagua. The road to these high mountain towns is sometimes

treacherous. We arrive in the early evening and decide to stay at Tubagua Plantation Eco Lodge, owned and operated by Tim Hall, a Canadian living on the island for 30 years. The cabanas here offer only subtle comfort

and breathtaking scenery. There are no TV’s, pools, bars, etc. just Taino style huts with few modern amenities. We dined with Mr. Hall and a close friend of his, Candis Krummel who works with Mayan Communities in Guatemala. Both commented repeatedly

that they were unable to comprehend the Dominican government’s position and denial of what appeared “clear as day” to them; that the Indian descent is everywhere in the Dominican Republic. I told them I was hoping to figure out the same thing.

May 23- Day 2- Tubagua We awoke early and met Fray Santana, the man who built the bohio (Taino Style hut) for Mr. Hall. Fray told us of all the mountain trails in the area and how he maneuvers from town to town

through them. He refuses to travel by car or bus through the main roads. He tells us that the mountain roads are old Indian trails. His knowledge of medicinal plants is quite impressive, but building bohios is his specialty. He informs us he learned

to construct these thatched-roof homes by watching elders. At first, he states he does not know much about Indians, at least not here in Tubagua. Later however he divulges information regarding Indians living further west and that there are many indios

on the island. AFTET: Ten years a team of geneticists headed by Arlene Alvarez, Director of the Museo de Altos De Chavon, located at La Romana, conducted a mitochondrial DNA sequencing analysis study in the area and gathered data that revealed

Native American ancestry in 33% of the population, In “Genetic prints of Amerindian female migrations through the Caribbean revealed by control sequences from Dominican Haplpogroup A- University of Mayaguez 2006. I visited

the area shortly after as I had never been to this region and met a young woman and her son, Paula and Adonis Martinez both of obvious native descent and spoke to them about their hometown, its history and customs. I took their picture and left. For years

I dreamed of revisiting them. Three days before I arrived on the island, a friend was able to locate the family for me. Since our first meeting they had moved from Tubagua

to the nearby village of Yasica Laja. Remarkably Paula seemed not to have aged. The young boy I met so long ago was now a full grown man of 20. I spoke to them about our project. Paula although genuinely interested, assured

me that her mother knew more about such things than she did. Her son Adonis on the other hand spoke of hidden caves in the hills with Indian carvings that no one knew about and that they ” called” him since he was a young boy. He has been

exploring the caves all his life. Paula’s uncle Bernardo a curandero (healer) spoke to us about his knowledge of endemic medicinal plants such as guaucil and tua-tua. He tells us that plant harvesting must be associated with a prayer. I left feeling

happy for their interest and happy that although poor, they are alive, well and quite happy. In her dissertation, Cultural Genesis, American historian Lynne Guitar writes “in 1555 four (4) entire pueblos of Indians were “discovered”

by the Spaniards in the Puerto Plata region (5 miles from Tubagua) these Indians apparently had escaped detection by Spanish forces during the contact period. Once “discovered” many dispersed to the nearby hills.” I strongly suspect it is

a good possibility, given the proximity, genetic evidence and clear native physical appearance found in abundance in this area, that many of Tubagua and Yasica’s residents are in fact the descendants of these four villages the Spaniards encountered in

1555.

Paola, and her niece

Revisiting Taino Family

Fray Santana

Tubagua Bohio buikder

Adonis and his mother Paola

I first met them on a research trio in 2003

Jorge and Adonis

Wow how he has grown! This is Adonis 10 years later and still identifying with his native ancestry!

Paola in 2013

It is as if time stood still for this Taino woman from Tubagua!

JARABACOA

The beautiful mountain country of Jarabacoa in the heart of the CIBAO

The beautiful mountain country of Jarabacoa in the heart of the CIBAO

May 24, Day 3- Jarabacoa We arose at 7:00 a.m. to get an early start towards the central mountains. Along the way we see many villages. I only wish we had time to explore them

all. Just as in Cuba and Puerto Rico, most of the villages have Taino names. We make our way to the Jarabacoa region, particularly the hamlets of Manabao and Atiyo. The countryside is amazingly beautiful. As we make it higher into the mountain, we notice the

difference in vegetation. Pine trees grow in abundance in this area. This is near the mountain town of Constanza near Pico Duarte, highest peak east of the Mississippi river. We arrived late to the hotel. We will explore the area early tomorrow morning.

May 25, Day 4-Manabao- “We have no Yuca”! We leave the hotel and continue further up the mountain. Once again, Even I am surprised at how readily one sees native physiognomy in the inhabitants.

We reach Manabao at 10:00 am. Once there, we have to take a detour through an unpaved road that will lead us to a small village we are seeking. We meet a woman and her son on the road. They look like they need a ride. They are traveling to a “misa”,

a Christian prayer circle. Remarkably they live on the opposite mountain and have been traveling all morning. We ask the woman if she knows anything about the legends of the “Indians in the waterfalls”. These legends according to Dominicans

are real and involve Indian spirits who reside in the rivers and streams. The spirits are said to occasionally capture and carry you under the river where they live. These stories are quite common throughout the country. She says “ yes I was carried

off by an Indian but was able to get away. I have been afraid to go near the water ever since” she says through very native eyes. This belief is reminiscent of beings called “jique” that are saidto live in Cuba. VERY TELLING INCIDENT:

She complains of not having yuca (manioc) and cannot make any more casabe (Taino bread). The high mountain is not good for yuca production. It is a big concern for her. Further, the hotels in the lower regions buy up all the yuca. Thus very little, if any

at all reach these mountain communities. The more we press her about the “WATER spirits” the more she tells us she needs to make her casabe. I get the sense we will find many good things here. We finally reach a road called

“la cienega”. Do doubt, the eye can be deceiving, but it is important to state that two out of every 3 people we encountered had strong native phenotypes. It certainly bears noting, even as we understand the fluidity of human

looks that some families here are so in the classic American Indigenous Amazonian and Caribbean, phenotypically as to appear to be “full blooded” An old man and boy on a horse pass by. He reminds me of photos of

Taino Cacike Panchito Ramirez of Caridad de los Indios, (BARREIRO-HARTMANN) in eastern Cuba. Porfirio Franco and his grandson Franci de Jesus Rodrigues are friendly and curious. They agree to speak to us about their town and let us film him. Don

Porfirio knows a lot about medicinal plants as does his young grandson. He proudly states he learned everything he knows from his grandfather. (Traditional endemic plant knowledge, Indigeneity Marker) I tell them

about our museum, our project and he is casually interested. I am surprised to find that, although he is brown skinned he thinks of himself as a Spanish descendant. I show him pictures of Indians, Africans and Europeans. He correctly guesses which group is

which. I ask him which group he thinks he belongs to or rather resembles. He gives me a long hard look, then smiles, turns his head and waves at a friend. I learned something. Point is accepted, but it ends the conversation! INTERESTING IDENTITY

EXPERIMENT. Back on the road we meet, Doña Elena Genao again stereotypically Indian in features. I HAVE HEARD

THAT SHE claims to have been abducted by Indian spirits as a young girl. She refuses an interview at first, but grants us pictures. I realize at this point that these people are all struggling and have little time for interviews and the like. I know now that

to open up a conversation I must offer something. The woman complains “we have no yuca”! I cannot make casabe and I am too old to travel to Atiyo (higo) where there is much casabe.” She turns and continues on her way. Everyone

we spoke to had the same concern, no yuca. CONCEPT OF GIFT-RECIPROCITY Further up the road we meet Maria Martinez Capellan who is collecting bottles in order to buy her mom a mother’s day

gift. The people here are great casabe eaters. I offer her a few pesos and she agreed to talk to us. She smiles and walks us over to a friend’s porch where we can talk comfortably.

At first she is reluctant to speak to us about the Indian SPIRITS in the waterfalls. She too complains about not having yuca to make casabe. Finally she insists that she knows nothing about Indians. I show her my pictures

but she is not remotely interested in them. We ask her questions about medicinal plants and casabe. She tells us she is a master casabe maker. Her knowledge of medicinal plants was also extensive. However , asking direct questions about “Indian”

identity or of a topic as “Indian” sort of stopped the conversation in its tracks. Consistently, as with several others in this type of research, I could not help but feel that there was something to explore about this no-and-yes about Identity.

A young lighter skinned boy sitting beside her jumps in and speaks to us about the Indians in the waterfall. He says he knows of one Indian man who lives further up the mountain, but other than that there are

no Indians. I ask him if Maria looks Indian to him. He smiles and says “no she looks like a nice woman, a regular woman”. He begins to tell us of water falls further away where there are Indians but that there are none here in la Cienega because

the Indians need water and the water in these parts has run dry. Despite her reluctance, Maria who is from a large, traditional family in the area begins to open up about a few things. It becomes clear that it

is her mother who was once abducted by Indio water spirits. We offer Maria a ride to her mother’s house which is about a mile away. When we arrive we notice some peculiar habits as she enters her mother’s home. She wipes her feet at the

entrance even though the home has a dirt floor. She puts her hand on the doorway and appears to whisper a prayer. We walk to the back yard where her mother is washing a plastic water bottle. Maria walks behind her mother who does not

acknowledge her until Maria gets on one knee and asks her mother for a blessing. Maria is a woman in her 60’s and her mother must be in her 90’s. (This is a very old kind of expression-respect) Her mother

introduces herself “Hi my name is Edubencia Capellan. All the lands you see around here are owned by family members. Most of us live right here in Manabao, some have moved to Santiago. My children were all born here but

I come from el Higo, a village in the adjacent mountains. When I was young I was pulled into the river by an Indian SPIRIT woman who was trying to seduce me and take me away. I was able to break free. She would sit there by the river

with a big comb and comb her hair.” Still she was very reluctant to speak about “Indio” directly. In her expression, Indians lived a long time ago and only their spirits existed and only rarely

these days. But then she proceeded to tell us about medicinal plants such as maguey, sauco, albahaca, auyama and medicinal corn. I felt rather sad to see such beautiful Indian people, who use a plethora of Taino words, look extremely native and practice a

myriad of Taino customs yet disconnect their way of life from an identity as Indios. In the monte, there is quite a serious stigma (shame) about claiming an Indian Identity. HAITIAN TESTIMONY: On our way out of the village we

meet an Afro- Haitian family. I ask a young woman if they make casabe. She replies, “ no we do not, we used to buy it from these Indians, but they do not make casabe here any longer. There is no yuca!” I am surprised that the Haitians called them

Indians. I ask them why they think they are Indians when these people claim to be white. She continues “ look at them, they are all Indians, they hide it, but they know they are Indians. We know what white people look like, look at them”! She laughs

and they all walk away. If you travel to the cities from the campo (countryside, there is a stigma associated with being campesino (peasant). In Latin America the

Indian has historically been seen as the lowest on the social ladder. The Indian when not glorified is demonized.Thus few people identified with the Indian outright in these mountains. At least that’s how I understood it. Later in this journey

I would learn more about how and why this came to be.

Helena Genao

Jarabacoa Native. Her main concern: Not enough Yuca to make Casabe!

Don Porfirio and his Grandson Franci

Porfirio and his Grandson had extensive knowledge of Native medicinal plants

Maria Martinez Cappellan

The Cappellan Family are a small family clan with amazing stories full of Indigeneity.

Edubencia Cappellan

Matriarch of the Cappellan family clan

Edubencia & daughter Maria, telliing us stories of Opia's, Ciguapa, Huracan and the most dreaded of all.......Baguada!

Edubencia & daughter Maria, telliing us stories of Opia's, Ciguapa, Huracan and the most dreaded of all.......Baguada!

HIGO

Haitian Woman living at the edge of Manabao

Haitian Woman living at the edge of Manabao

MORE “MONTE ADENTRO”: EL HIGO It is still early so we make our way towards Atiyo. This small village is approximately 10 miles away. I would guess that no more than few thousand people

live in this area. We arrive in the late afternoon. Here at Atiyo there are small roads that lead to villages, one is called “el Higo” where Edubencia was born. We travel down the mountain and make it to the adjacent community. As soon as we enter

we realize we will have to park the car and walk quite a bit to make it to the village. We get there and immediately ask people we meet, is there yuca? Is there Casabe? Everyone responds….. yes! Every family in this village makes casabe.

Much like the people of Cacike, Moncion, west of here, casabe is central to their economy. The people of the Manabao Region make a monthly pilgrimage to Higo to purchase casabe. The Higo people are very

proud of their casabe style which is smaller and thicker than other regions and the taste is divine. The mestizaje here is obviously Afro-Taino. With many of the more classic Indigenous phyisonomy, again looking puro “Indio”Here I interviewed

Carmen Dominguez and her family. Carmen and her husband Jose both grow the yuca and process it into casabe bread as does their entire family and neighbors. The yuca grows well

at this altitude. She takes us through the process and I, who was raised making casabe and am familiar with the techniques and terms associated with the process (all of which are in Taino) am surprised to learn three new Taino words! Cuisa:

small wooden spatula used to turn over the casabe bread. Jamarica: same as Cuisa only made from the bottom shell of a fresh water turtle. Cuyabei: large chunks of yuca left over after yuca has been grated on the guayo (grater).

Note: Need to compile al new words into a report and break down” markers” of Tangible and intangible culture.. The Dominguez clan refers to their ancestors as Indians. It began

to dawn on me that perhaps the Haitian girl we spoke to was right. These mountain people know more than they let were letting onto. We film and photograph them, buy some casabe, say goodbye and promise to return one day.

At

the foot of the mountain we meet a man selling mamajuana by the road. This concoction of endemic roots, twigs and leaves is used as a cure all has been attributed to the classic Taino. It is often mixed with rum or tequila. People claim

it is an aphrodisiac and jokingly call it “the baby maker”. We interview him briefly and we are on our way. We are headed to Santo Domingo, capital city. We arrive late in the evening. May 26- Day 5- Santo Domingo

No hotels in Santo Domingo with a parking lot for our car and gear. We are forced to stay at a noisy yet comfortable Hotel and Casino. For a people struggling with money and lack of jobs, the casino sure is packed full of people nightly. TAINO

ACTIVISM: IDENTITY MOVEMENT Today we will interview members of Union Higuayagua a Taino cultural group. Boasting a membership of some 400 individuals , with at least 120 fully active members spread throughout

the country, I rely on them to keep me posted on events taking place on the island and on all Taino cultural manifestations. Our primary mission and focus is to unite all groups, organizations and individuals on the island who identify with their Native heritage

and are active in all sorts of issues affecting the island. Guide and camera man, Boynayel Mota for example is leading a campaign against some unscrupulous vendors who are catching, selling and eating endangered endemic species on the island. In this

case, Manatee, Dominican Green Back Boa and our species of fresh water Hicotea (turtle). We begin our interview with Luis Francisco Garcia also known as Gui-Gui. Very funny and quite the character, he immediately states “I

am Taino, my family is Taino and I want the world to know that the Taino people of Kiskeya are still here”. Gui-Gui is originally from the province of Higuey although he also has roots in San Juan de la Maguana.

Next we speak to Cacike Leonel de Jesus Melo (Kayacoa) who is originally from Higuey. The people of Higuey are very proud of their Taino ancestry and are quick to tell you so. Kayacoa has been active as an artist and formed an organization

of artisans, Taino Reservation. He has helped me enormously on this trip, has many connections, knows many locations and has a large following of people in his native province. We finish up late in

the afternoon with Salome Anarix Ureña. Salome is a die-hard Taino woman who is not afraid to speak her mind, although a bit shy in front of the camera. Her dedication to Taino culture and Identity are very strong. She is a school teacher and is dedicated

to showing her students the truth about their history. She hails from the Cibao region, near Manabao. The Higuayagua group was founded in 2010 and has members all over the country. This trip indicated a need to step up our efforts

in communities throughout the island. Tomorrow we travel to Azua.

Dominguez Clan with Jorge B. Estevez

Casabe making village of Higo. The entire village makes Casabe.

Carmen Dominguez

Master Casabe and Boyo maker.

Daria Dominguez

Daria looks on as her cousin Carmen prepares casabe

Higuayagua Member Salome Anarix Urena

Anarix is a founding member of Higuayagua going back to 2008

Leonel de Jesus Melo, Jorge Estevez and the late Gui Gui. He will be missed forever.

Leonel de Jesus Melo, Jorge Estevez and the late Gui Gui. He will be missed forever.

AZUA & MAGUANA

Young Azuan boy selling Cactus by the road.

Young Azuan boy selling Cactus by the road.

May 27- Day 6- Azua IDENTITY REVIVALS: CORE AREAS Today we arrived in Azua a region and town known for its high level of Indian identity. This is also the place where inhabitants

have revived the ancient Taino ball game of Batu. Similar to the Aztec game, Ulama , participants hit a hard rubber ball with all body parts except hands and feet. We arrive late in the afternoon and find that the players

are not prepared to play for us. Somehow our communications got crossed. We were able to get a demonstration from some players, but not in Taino regalia as is their custom. Also we spoke to the director of cultural center, Rannel Baez.

Rannel was very polite and chooses his words carefully. He expressed his desire to work with the

NMAI but cautioned us that due to the political situation on the island, they do not refer to themselves as a Taino cultural group but rather a folkloric/performance group. SHAME-FEAR COMPLEX. He mentioned a bad experience they had in Puerto Rico with

one of the local Taino groups in which the Puerto Rican group could not understand why the Dominican group would not identify as Taino openly. Before the Azua group left for Puerto Rico their regalia was confiscated by the Dominican authorities

and were warned not to identify as Indians! Asserting Native-ness can bring you unwanted problems from the authorities. IS THE RELUCTANCE to identify as Indians in Manabao and Tubagua SHAME OR FEAR OR BOTH? We head

back to Santo Domingo. We are advised to visit nearby Pueblo Viejo, where there is an enclave of Taino descendants, but it is late and we must keep to the schedule. The heat and all the walking is getting to me. May 28- Day 7

We head out early to San Juan de La Maguana which is 4 hours away. For this portion of the trip we are joined by Milton Sanchez Velazquez and his wife Ivel, both Taino-identified. Along

the way we pass by Azua again near Pueblo Viejo and meet a young Taino boy. His mother is busy working on the side of the road selling Guanime which is a traditional Taino food. She is reluctant to grant us an interview. We ask them if they are Indians

and they say yes as many people in Azua do. It feels like this portion of the trip will give us positive results. With pride, she grants me permission to photograph her son. Arriving in Maguana in

the late afternoon during a heavy rain, we decide it is best not to trek up the mountains under these conditions and will wait till morning. We rent out a hotel room which looks like something out of the old wild west. May 29- Day 8- San

Juan de La Maguana I have waited years to visit Maguana. It is one of two regions I have not visited in the country. Our first stop is at the Corral de Los Indio (Indian Coral) which is a Taino ceremonial ball park. This place

contains a large stone upon which a Taino national heroine, Chief Anacaona is said to have recited her poetry and songs during Areito (social gatherings). The stone is at the center of the plaza which is some 750 feet in diameter, largest in the Caribbean.

We are hoping to meet Amantina, caretaker and spiritual leader of the place. Here in Maguana Indian heritage is taken very seriously and expressed openly. People are not

only Indian Identified but also believe that Indian ancestral spirits inhabit the area, the rivers, caves, trees etc. Amantina has been guarding the stone all her life as did the woman before her and the woman before. She does not generally grant interviews;

in fact she rarely shows her face to outsiders. Not that she does not want to, rather she must be guided by Anacaona’s spirit or Indian spirit guides to do so. I am worried that after traveling for so long she may not want to meet us.

My fears were quickly extinguished when she walked out her home which is at the edge of the plaza and says “welcome! I have been waiting for you for a long time. Please come in we have lots to talk about!” I am grateful and

perplexed as I had never met her before. In fact I had only heard of her in passing from Irka Mateo, Dominican Taino folk singer and NMAI collaborator. Although most of the people that we have met thus far are warm and friendly , here in Maguana it seems to

be a custom that all practice every chance they get. Amantina takes my hand and guides me to her altar. Her alter is syncretic in nature as it has Taino/African/Spanish elements. She begins by telling us that the “mysteries”

as this spiritual practice is called, are happy we have arrived. She rings a bell and sprays a sweet smelling mist into the air. “Ernesto Cintron” has been my helper in keeping Anacaona’s stone safe and clean. He also gave me this stone

(reaches for a small stone) which has traveled the world. Some people say there is nothing here, Haitians, Evangelical, people from other countries and so on, but the truth is that the mysteries, those Indian spirits that reside here and our queen Anacaona

only make their presence known to those people they deem worthy”. As I listen to her I pick up Christian elements and am reminded of Santeria. Just as in this African based religion it is as though Taino deities were given names of Christian saints and

angels in an order to hide our religion from the Europeans. Surely any catholic who visits this altar would be aghast at the un-Christian way these people worship. We interview her and ask for permission, as is the custom, to go

to the stone and offer some prayers. She responds “certainly, but I cannot go with you. Anacaona she has been waiting for you for a long time”. This statement caused deep feelings in me. For over a decade if not longer I have been hoping

to come to this place, perhaps more like a calling. For years I was unable to return to the Dominican Republic for a variety of reasons though. One member of our group brings out a mayowakan (Taino log drum) and begins to

play. Suddenly Amantina says “it really is you! You are truly the person I was waiting for”. Of course I will go to her stone with you”! We walk towards the stone, one we can all feel the energy of

this sacred space. We reach the stone and begin our ceremony. Smoke is blown to the four directions as Amantina performs a silent ritual. Afterward we all embrace in solidarity. She tells me Anacaona is happy. Suddenly one of our group notices these strange

circular patches of what appear to be crop circles forming on the ground! They are in all sizes, some with a 20 foot circumference. They are shaped like bohio’s. At this point I feel the need to gift Amantina a headdress I brought with me. I put

it on her head as this big gush of wind envelops the ball park. She smiles and says “Jorge you and I have so much to talk about, there are secrets here, secret brotherhoods that will welcome you when you return. You will find all the answers to your

questions here”. If it were up to me, I would have stayed in Maguana and learned as much as I could from Amantina, but there are more places and people to visit. We continue towards the sacred center of the “Aguita de Liborio

in the mountains. Maguana is often called the Taino capital of the Dominican Republic. Locals know it as the “belly button of the world”. There are daily pilgrimages from all over the island as most shaman, curandero and brujos live here. One can

witness people in early Morning Prayer “lifting up the Sun”. This is also the birthplace of Dominican Republic’s most important Messianic figure, Liborio Mateo. Followers of his religion travel here to bathe in a sacred water spot where he

drank and bathed while pursued by American and Dominican forces from 1916 to 1922. After being betrayed he was finally captured and killed. He is also credited with unifying Taino, African and Christian religious beliefs into one cohesive unit. This is known

as Liborismo. People believed he could wake the dead and communicate with ancestral spirits. He was also the incarnation of Caonabo (Taino Chief and husband of Anacaona) and St. John the Baptist. His story is quite long and fascinating.

After arriving at the Calvario (three crosses) we were asked to circle it three times, place a stone on the cross and then enter the altar. Hernandez and his wife Carmen are the caretakers of this place. Hernandez is inside by the altar with a young woman

who has been “mounted” by an Indian. He is guiding her and telling her not to fear them. The young woman turns towards us and we notice she has strong Indian features. We are not allowed to take pictures of her face, only of her back.

Finally we are able to speak to Hernandez de la Rosa Popa. Both he and his wife are actually from another region, Las lomas de Cabrera (near my hometown of Jaibon ). They immigrated to Maguana after receiving a spiritual calling to carry on

the work of the previous caretaker, Reina, who passed away 12 years ago. A typical prayer goes like this “in the name of the Father, Son holy spirit and Chief Anacaona”……. The Calvario, Altar and Aguita de Liborio are huge responsibilities

which they take very seriously. Hernandez begins, “thank you for coming to my humble home we welcome you as brothers and Papa Librorio is honored for your visit.” He agrees to the interview. He explains what he

does and why he does it. How this is his life’s work and is preparing the next generation of caretakers. When the topic of Indians is brought up he continues “Honestly, speaking of Indians is hard, I am not really supposed to share such things.

What I will say is that many people have a calling and Indian spirits enter and guide them. This is very real; I myself have encountered Indians in life and in dreams. They remind us of how to take care of the land and each other.” He motions for us

to turn off the camera, takes a moment and continues, “there is not much more I can say, but the Indio’s are real, they are everywhere. I must head out to Santo Domingo, the young woman has an Indio in her and he will stay there until she prays

over her uncle’s body (he passed away the night before). Please stay and have something to eat. My wife Carmen will answer any questions you may have.” He smiles, turns and leaves. Carmen de la Rosa Popa is an interesting

woman. She has very light skin, aquiline nose, long straight hair and high cheekbones. She looks like many South American mestizos I have met before. She tells us about medicinal plants, how they are planted according to the moon cycles. Also you must

offer a prayer when you plant them as well as when you pick them. The topic of Indians spirits and Ciguapa comes up. Ciguapa are creatures that live in the forest and mountains. They have long hair and inverted feet, making it difficult to track them. Most

Indians of the Cir-cum Caribbean region also believe in this creature. It is known as Ciguanama in El Salvador, Currupia in Venezuela and Caipora in Brazil. I ask her if she thinks these are actual Indians and she says “no, they are not exactly like

us, although many believe they are wild Indians”. Carmen then prepares a “huso” (drop spindle) made from a small stick and an “ojo de buey” seed. Earlier at Maguana children had picked wild cotton for

us. Carmen spun this very cotton into thread. It was truly amazing. We eat and continue to the Aguita. Once at the Aguita we say our prayers at the altar and then wash in its sacred waters. There are many pilgrims there this

day. Indeed this place is magical and strongest in Indian lore. My only regret is that we were unable to go further up the mountain and into the National Park, which is huge and many parts barely explored. The terrain did not lend

itself to our vehicle which was a loan and in bad shape. To get there we had to rent mules and travel 9 hours up the mountain. I was told there are many Indian villages there and denial of the Indian is non-existent. I know I must return on my own and re-visit

this region. It actually hurts to leave these beautiful people. I say a prayer and give thanks to the four directions, to the people of this village, to the NMAI, Machel Monenerkit, Jose Barreiro and Rosita Estevez for sending me on this trip and I pray

that my friend and co-worker Carolyn Rapkevian has a speedy recovery. I have never felt as connected and accepted as I have been in Maguana

Amantina

Amantina holing her healing stone. These stones have been used for healing since pre-contact times

Carmen Popa

Carmen is the head of the Liborista Mission. Liborista religion is mostly Catholic and Taino.

Anacoana's Stone

Sacred stone visited by many islanders. The stone i said to be the sitting place.

Prayers

Cacike Baracutei Concatecuax Bl;owing tobacco smoke to his ancestors.

Young worshipper

Young woman about to receive an ancestral spirit. All the spirits received are Indigenous to the island.

Amantina

Amanitina after receiving a headdress as a gift from Cacike Jorge Baracutei Estevez Concatecuax.

Taino Abinaka (dancer) from Azua

Taino Abinaka (dancer) from Azua

Higuey

Cacike Holding an Indigenous Rhino Iguana

Cacike Holding an Indigenous Rhino Iguana

May 30-Day 9-Higuey Rise and shine, onward to Higuey at the far eastern end of the island, a very long ride. We will make a pit stop at Santo Domingo to interview Rafael Garcia Bido. We arrive late in the afternoon.

Traffic was horrible. We rescued a baby rhinoceros iguana from a young man selling it by the road. These lizards grow to almost 6 feet in length and are only found in the Dominican Republic. I offer the young man 500.00 pesos ($12.50) which is a lot of money

to him. We drive down the road and release it. Dominicans are very astute, we joke that perhaps he has trained the Iguana to return to his home after the purchase and release! Rafael Garcia Bido is an Architect by trade but his

passion lies in linguistics. He has been studying the Taino language for over 20 years now. When the Spanish arrived on the island they took note of Taino words, some of which made their way into Spanish. But how many un-recorded words of Taino extraction

are still in use today? No one has ever attempted to do this work, until now. Mr. Bido has recorded 700 Taino words found throughout the island that were never recorded by the Spanish and are in fact of Taino Arawak origin. Words such as Maniao and

Tabiao (arms and legs) and Uiku (fermented beverage made from the poisonous manioc juice are just a few examples of words used in this country that are not Spanish. Rafael grants us an interview and makes this very

profound statement, “everything that is going on today was planned by our ancestors. When the Spanish pushed the population towards Higuey (where the last major battle between Taino and Spanish occurred) the people gathered in the sacred mountains and

decided that it was better to fight the Spanish from within, or rather join with him rather than continue fighting them. The hope being that one day Taino consciousness would re-awaken and re-claim our culture. Apparently this is exactly what is happening

today all over the Caribbean”. His words resonate in me. I understand what he is saying. My supervisor, Jose Barreiro framed our entire research project around Indigeneity and consciousness of Taino. I am witnessing first-hand the re-awakening of the

people not just on this island but throughout the Caribbean. He continues: All the sacred sites on this island are ruled by Indian spirits. These guardians are very strong. In order to connect spiritually to this place Africans

had to forge an allegiance with them. It is this bond that helps usher in a new generation. In this time the Indian and African, side by side and within one another will bring the light back to the people. This is what the “brotherhoods and sisterhoods”

have been working towards for a long time now. This reference to secret societies is interesting. One of my goals for this trip was to interview people that belong to them. It is not easy. These people clam up as soon as they feel they

are being questioned about such thing, yet I felt a certain acceptance from all I met and suspected of being a part of one of these secret spiritual sects. What is certain is that they exist and further study must be made. I got the sense that many feel, the

time is right for “Taiba” to bring out and share. We say goodbye and continue on towards the Higuey region, our last stop on this amazing journey. After 5 hours on the road we arrive in Higuey just

past midnight, find a hotel and go straight to sleep. I cannot wait to see what Higuey has to offer. June 1-Day 10- Higuey! Today is our last day. I am determined to make the most of it. Our first

stop is Boca de Yuma Cave. This cave is rumored to be the place where the Taino people emerged. According to our legends, the Taino people made their way out of a sacred mountain and emerged from a cave called Cacibajagua while everyone else in the world exited

via a cave called Amauyana (non-importance). Boca de Yuma is a huge cave with two exits. They certainly fit the description of the caves the Taino spoke about. The walls are covered in Taino petroglyphs. We explore the caves and take pictures and offer some

tobacco. Just as we are leaving two men approach the cave. Jose Rosario Gomez and Francisco Cedeño are park rangers. They make their living by guiding people through the caves.

They are both very knowledgeable of medicinal plants .Mr. Gomez begins by telling us that he has guided people through the caves for 30 years. We ask him about several questions: What do you know about Ciguapas? “Oh

there are no…..no such things as ciguapa! I can only recall one time when I was a young boy of 13 years of age seeing a ciguapa. This was in Macorix where I am originally from. At that time Presidente Trujillo’s men

captured a ciguapa couple with child. They let them go but kept the baby. No one knows what happened to the baby. Ciguapa are afraid of dogs. It is customary to bring dogs with you when walking in the mountains or forest.” I do not dare remind him that

at the beginning of the conversation he swore there were no such things as Ciguapa! I actually encountered that a lot on this trip. What do you know about medicinal plants? “well, there are many kinds of plants here.

There is Anamu, mamajuana, chinola, etc. All are good. Many are found around the caves in this region. I know many of them, ask me about anyone you like.” About Indians: “Well Indians are different than we are.

They are more cooperative with each other. For example if a group of us today are doing something, one of us may want to go in one direction and the others in other directions, but Indians are different in that when one says “this way” the rest

followed him”. I explain the NMAI-CILP project to him: “Oh! This is good! The Indian is inside Dominicans today. We carry him in our blood. The Indian will return. This country cannot go on this way.

It is our Indian blood that helps us understand and respect the land and its resources. One day, we will return to the Indian. Of that I have no doubt”. I ask him another question about a plant known

as saraguey. His companion, Jose, interjects in what sounds like Cuban Spanish: Do you know Saraguey? “You must mean rompe saraguey. Yes this plant is very important to us.” He gives us descriptions

of various plants and their uses. I ask him if prayers are ever offered when these medicines are picked. “Not only do you pray to pick them, but also when you plant them! There is a procedure you must follow. You have to give thanks

to god. Then you must knock on the ground three times. The same procedure when they are picked. Some plants can only be picked at noon, some only at night. This is extremely important. About Indians: “We

all have Indian blood. I for example have a lot of black blood, but I also have Indian. Everywhere you travel in this country you will always encounter people that look like Indios and they are. Just as you mentioned a while ago, the Indian can never be erased.

I am proud of my Indian heritage. There are many things we do that we would not be able to were it not for this blood.” He goes further, “people make pilgrimages to this cave from as far away as Haiti and leave fruit and casabe bread in gourds.

That is the blood that calls and guides you.” I thank them both for a very interesting interview. But it is getting late and we need to get to Anamuya Rock before it rains. Our

guide for this area, Leonel de Jesus Melo, does not quite explain why though. Anamuya means flower-thread in Taino. Why this rock was named thus is unknown to me. The

rock is on the ground and is about about25 feet long and about 10 feet wide. To get to the stone we must drive up a long winded hill. The road is treacherous as are most of the roads we have traveled so far. Gratefully we are not on another mountain.

We drive as far as we can. The rest of the trip is on foot. We leave the car by the side of the road where there is a Haitian “batey”. Batey is the Taino word for ballpark, but these days it means any hamlet or village where there is a concentration

of Haitians immigrants. We ask permission to leave the car there and it is granted. We make our way through the forest to a river. Here Leonel shows us some petroglyphs that have

been ignored by investigators. The tide is low and we can hop across the rocks to get to the other side. If it rains however, we are trapped there. Naturally I was the first to fall. Luckily the rest of our party fell too so embarrassment was minimal!

On the other side of the river are many head of cattle. We make our way to the sacred rock. It has been cordoned off so that the cows will not defecate on it. There are magic mushrooms growing

everywhere. Once inside the area, I am amazed at the complexity of these glyphs. I decided to blow smoke to the four directions. I ask where the north is, as there is no one more directionally challenged than I. Coincidently I am standing by a curious

glyph that looks like a four leaf clover with a cross in the middle. It is different from any glyph I have ever seen in the Caribbean. As I begin turning to face the east, south and west, our cameraman Boynayel Mota yells “Tiao (brother) step inside

the petroglyph!” I do so, and realize that this glyph, which fits my feet is perfectly aligned with the four directions. Oral tradition tells us this was a meeting place where the behike (medicine

people) gathered for ceremonies. I am tempted to think that perhaps this is why there is so much Psilocybin Cubensis in the area. Then again, the cow dung where it grows may have everything to do with this as well.

We head out to a Taino cultural center where the owner has recreated a Taino village. Along the path endemic plants are growing. They have several large Iguana in an enclosure. The village is aligned with Bohio

(Taino thatched roof houses) which are identical to the homes of modern day descendants. Here we meet a man named Hungo. No surname, just plain old Hungo. Unapologetically Hungo declares “ I am Taino, I don’t care what anyone

says about it. All my family is Indio. He follows up this claim by answering all our questions regarding plants, basket making, hammocks and ciguapa and so on. He truly has knowledge of all sorts of Taino cultural expressions. I wish we had more

time to spend out here , but sadly our trip has come to an end. We head back towards Santo Domingo and then on to Santiago in the North where my flight departs from.

Mouth Entrance

Yuma (Mouth in Taino) is a cave where a great massacre occured.

Petroglyh

Ancient Taino Rock art!

Jose Rosario Gomez

Mr. Gomez is a protects the Yuma cave and has many ancestral stories

Francisco Ceden0

Guards the Yuma cave as well. This man knows the history of the region better than most!

Cacike Baracutei Concatecuax

Jorge and a Traditional Casabe Buren.

BONAO

El Tajo! Proud Indian man

El Tajo! Proud Indian man

On the way to Santiago we pass the town of Bonao. Every other town, valley, river or mountain has a a Taino name. I can’t get over how amazing this is. We notice a man selling Batea’s by the side of the road. Batea

are oval or circular wooden trays used by the classic Taino to carry food, wash clothes or pan for bits of gold. Dominicans still make and use them for these same purposes and still call them batea which is its traditional name. We pull up and the

owner comes towards us smiling. “welcome, please come in. There is fresh coffee if you like.” Indeed everywhere we visited, these poor people freely shared everything they had. Christopher Columbus described these manners and customs among

the classic Taino as well. “They call me Taho he says.” We introduce ourselves and tell him of our investigation. Tajo seems like a quiet man of simple means. But Taho is actually very quick minded and smart.

He says, “good, very good, very happy you are doing this work! I am Indian, my children are Indian as was my father and his father. Of course I will tell you about batea…… Oh here comes my wife. She too is

Indian.” I am floored because after officially signing off the project, we meet Taho. A must interview. But the truth is that in the Dominican Republic, Indigeneity is

found everywhere. Heavily concentrated in some areas, sparsely in others, but everywhere. Tajo tells us his grandfather found a batea in a cave when he was a young boy. He copied it and remained faithful to the craft and taught it to all his family. I really

like Taho, especially after he tells me he Is from la lomas de Cabrera, near la linea, the region my family comes from.. Towns such as San Jose de Las Matas, Jaibon, Laguna Salada, Mao, Cupey etc are known for their high retenion of Indian blood. Taho felt

like family.

|

|

|

|

|

|