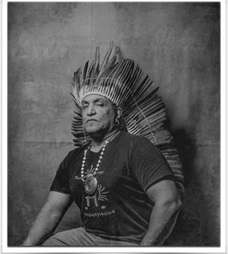

Kashikwali Atunwa

Jorge Baracutei Concateciuax Estevex

Kashikwali Atunwa

Jorge Baracutei Concateciuax Estevex

The Taíno Head Dress

FACT:

"With the exception of certain gender-specific gender ritual regalia, headdresses can be worn by any gender. One of the ways we know this is by

the practices of our Arawakan relatives."

Jorge Baracutei Concatecuax

by Taína

Along the journey to reconnecting with our Taíno culture we will surely encounter

questions about arguably the most iconic symbol of Indigenous People— the head dress. Especially in our current societal climate, it is more important than ever to understand our ancestral traditions and their origins, in order to practice these traditions

respectfully. Recently, I had the chance to ask our Cacike Jorge Estevez, who himself has made over 900 hundred head dresses, about the origins, modern usage, and creation of Taíno head dresses, and this article will hopefully answer all you ever wanted

to know about the Taíno head dress.

When asked if the Taínos wore head dresses, Cacike’s answer was a loud and clear, “Unequivocal YES!” Due to the depictions of Taínos with short hair in the front, and long in

the back this has been a subject of much debate. “Higuayagua prides itself on using Divine Academic Inspiration,” Cacike explained. This means research is done on every aspect of our culture, instead of relying upon Spanish narratives as doctrine.

These narratives are used as clues, to help supplement and inform in-person interviews with our closet Arawak relatives. As such, there is a significant amount of evidence that tells us our ancestors wore head dresses.

Christopher Columbus’ accounts,

make many references to the head dresses worn by the indigenous people he encountered in the Caribbean.

On his second voyage, Columbus and the Son of Caonaboa visited Andres Bernaldez at his rectory in Palacios. Accounts say he brought with them the

Feathered Crown (Headdress) that was said to have belonged to the Elder Caonaboa:

“He brought some crowns with wings and in them and between them some eyes on the sides of gold and especially he wore a crown that was very large and tall and had

on the sides being touching wings like a buckler and gold eyes sized like cups silver half frame, each one seated as enameled with very subtle and strange way and there the devil appearing in that crown and believe that this is how it appeared to them.”

During his trip to what is now known at The Dominican Republic, then called Marien, “Cacike Guacanagarix and 5 of his subordinates (Nitaino) visited Columbus on his ship. Later when Columbus went on shore, the Cacike placed his Feathered Crown on

Columbus head. This crown was adorned with feathers and smelted gold.”

Accounts of Andres Bernaldez (1450-1513), the priest on Columbus’ ship, and their year stranded in Jamaica tells of being greeted by a Taíno family in their regalia:

“A canoe came out to Columbus’ ship in Old Harbour Bay. In the prow stood a Standard- bearer clothed in a Feather- Mantel (Cloak) and with a “tuft” of bright color on his head. In his hand he carried a standard with flutterin white

pennant (Banner). The Standard bearer was followed by two (2) drummers (Mayowakan) who wore capuches (hoods) made of feathers and their faces were painted just as the standard bearer was. Two other Indians carried trumpets (Fotuto) made of black wood and carved

these wore Crowns of feathers on their head (Headdress). In addition there were 6 Body guards with white crowns (Headdress)”

Artist, Edward Velez, compared Mayan and Aztec art to Taíno Cemi artifacts, in a study you can see here, to illustrate

that while the Mayan and Aztec gods were depicted in the same clothing as the people, the Taíno artifacts depict the Cemi wearing a head dress. Perhaps the most compelling evidence, however, is that most Arawakan people use a head dress today.

Like

Arawak, the Taíno language is descriptive, and is essentially composed of a string of suffixes used to describe a concept. In Taíno, according to Cacike Jorge, head dress is known as “cachuichatina, cachuchabana, or plain ole cachucha”,

the last of which you might recognize as a slang term for baseball cap.

It is crucial to draw a distinction between the Taíno head dress, and the War Bonnet used by some North American Indigenous tribes. In these tribes, War Bonnets are worn

only by males, and are created entirely of primary Golden Eagle feathers, that have been blessed, and gifted by the Chief or Medicine Man for acts of valor, or war deeds. These are not the head dresses of young men. The incredible power of these War Bonnets

makes them deeply spiritual relics. Cacike Esteves says, “To wear such a head dress causes the hear to beat with the pride of the love, respect, and honor of the tribe.”

In the Taíno culture, cachucha, can generally be worn by either

gender. There are exceptions, however, for gender specific headdresses worn during certain rituals. For example, A young man will never wear the head dress a young woman wears during her First Moon ceremony. The most common type of head dress can be made of

a variety of feathers, and can be purchased, commissioned, and gifted according to rules that vary between tribes.

There are some types of cachucha, however that must be earned, like one worn by our Cacike Jorge Estevez. Made for Medicine ceremony,

his is a two-side head dresses made almost entirely out of Harpy Eagle feather. While the eagle is known to be one of the highest flying birds, and therefore the one with the highest vantage point, the Harpy Eagle is the strongest, and most ferocious of species.

When the ceremony begins the head dress is worn with the brown feathers facing out. When he ingests the medicine, it allows him “to soar high above the clouds, and people and animals” according to Cacike Esteves, in order to achieve an eagle’s

eye view. During the ceremony the head dress is reversed, to represent the wearer essentially “becoming the Harpy Eagle” revealing up to five central red macaw feathers, symbolizing the color of life itself. These head dresses are not earned through

war deeds, but through spirituality.

The head dress we see on our Cacike in the National Geographic article, “Meet the Survivors of the Paper Genocide”, was one he made himself, choosing and arranging feathers to reflect his ancestry. The

feathers in the front, and on the top were of a particularly powerful blue hybrid bird, which he chose to represent the modern Taíno people. Each head dress makes its own statement, and has its own meaning within the context of the style. This head

dress represents that “we do not see ourselves through a blood quantum lens,” says Cacike Jorge. “We understand and acknowledge our mixed blood heritage…We are in-situ in the Western Hemisphere. Our ancestors absorbed the outsiders,

not the other way around.”

The most common head dress can be made from a variety of feathers, which varies from tribe to tribe, along with the rules on who is allowed to wear them, and when. However, there are some common symbolisms across the

culture. For instance, the central tail feather, of a bird, is the most powerful feather, followed by the primary wing feathers, the secondary wing feathers, and the down feathers.

The feathers for Higuayagua, chosen based on suggestions of Arawak and

Pataxo relatives, and because theirs are the colors of the water, trees, land and sky, or as Cacike puts it, the abodes of the ancestral spirit, are; all parrots (i.e. Macaw, Conure Amazons), hawk, goose and duck. Eagle, vulture, and owl feathers are reserved

for Behike only.

In our tribe, members of our dance troupe are gifted their first head dress after proving their commitment by rehearsing, and dancing with the troupe four times. They can be purchased by contacting the Behike directly. All proceeds

from head dress purchases returns directly to the tribe, which allows Higuayagua to operate without charging for regalia or membership fees.

Whether or not a head dress is appropriate depends on the occasion. Council meetings, festivities, like Areito,

meetings between delegates, and certain spiritual ceremonies, are places wear head dress are commonly worn, but “It’s always a good idea to ask the leaders,” our Cacike advises. “For the most part we encourage our members to wear their

regalia, and head dresses” to marches for BLM, Women’s and LGBTQIA marches, protests, and events where statues of our colonizers are being torn down. Cacike Jorge’s final advice though, is that “Head dresses are rather fragile. You

can’t wear them just to look pretty every day. Think of them as your Gucci or Prada.”

To make a head dress you will need three types of cotton threads, jute, and anywhere between 25-70 feathers. The number of feathers will depend entirely

on the size of the head dress. A small crown can take 25-30, whereas a halo head dress can take 35-40, and a long one can have as many as 75 on each side! Don’t run off to the internet to buy your feathers, though. Traditionally feathers are sourced

through hunting, but, according to Cacike Jorge, “this destroys half of the feathers’ cemi (spiritual energy).” Since the most powerful feathers are those that have been gifted, or dropped naturally from the bird, Higuayagua prides itself

on sourcing its feathers from from aviaries and sanctuaries where birds are not harmed. For purposes of learning, and practicing the art of head dress making, drinking straws are an excellent substitute for feathers.

If you want to learn more about

head dresses, and how to make your own, Cacike Jorge Esteves will be honored us with a lesson on how to make a Taíno head dress. The video will be shared soon. Find more info on this as it becomes available, and stay up to date with all of the tribal

announcements, on the Higuayagua Facebook page

SOURCES: